How to Use Git

Git Config Setup

The git config command can be used to change your Git configuration.

$ git config user.name "John Doe"

# To set your username for a specific repository

# Type the command in the root folder of your repository

$ git config user.name

# Verify the setting

John Doe

$ git config --global user.name "Billy Everyteen"

# To set your username for every repository on your computer

$ git config --global user.name

# Confirm that you have set your username correctly

Billy Everyteen

$ git config --global user.email "john_doe@example.com"

# Set your email address

$ git config --global user.email

# Verify$ git config --global credential.helper cache

# Set git to use the credential memory cache

$ git config --global credential.helper 'cache --timeout=3600'

# Set the cache to timeout after 1 hour (setting is in seconds)$ git config color.ui true

# Use colorful git output

$ git config format.pretty oneline

# Show log on just one line per commit

$ git config --global alias.lol "log --pretty=oneline --abbrev-commit --graph --decorate"

# A nice alias you can set up which shows abbreviated commits and a nice graph of branches with the messages on a single line

$ git lol

* 7f84961 (HEAD, tag: v1.1.0, tag: to-be-tested, master) repeat

* df8a5bd add emphasis

* fe876d7 initial commitThe complete configuration is visible using git config -l, and the git-config man page explains the meaning of each option.

$ man git-config

# or

$ git help configTroubleshooting

My name doesn’t show up on GitHub

If the email used in a commit matches a verified GitHub user account, the account’s username is used, instead of the username set by Git.

If you have any local copies of personal repositories you have created or forked, you can find your username in the URL of the remote repository.

$ git remote -v

# Show URLs of each remote server

$ git remote show <name>

# Give more details about eachNew commits aren’t using the right name

If git config user.name reports the correct username for the repository you’re viewing, but your commits are using the wrong name, your environment variables may be overriding your username.

Make sure you have not set the GIT_COMMITTER_NAME or GIT_AUTHOR_NAME variables. You can check their values with the following command:

$ echo $GIT_COMMITTER_NAME

# Print the value of GIT_COMMITTER_NAME

$ echo $GIT_AUTHOR_NAME

# Print the value of GIT_AUTHOR_NAME

$ echo $GIT_COMMITTER_EMAIL

$ echo $GIT_AUTHOR_EMAIL

# If you notice a different value, you can change it like so:

$ export GIT_AUTHOR_NAME = "Billy Everyteen"

$ export GIT_COMMITTER_NAME = "$GIT_AUTHOR_NAME"

$ source ~/.bashrcMy old commits still have my old username

Changing your username in Git only affects commits that you make after your change.

To rewrite your old commits, you can use git filter-branch to change the repository history to use your new username.

A Common Git Workflow

This tutorial explains how to import a new project into Git, make changes to it, and share changes with other developers.

By default, the first branch on any git project is called “master”.

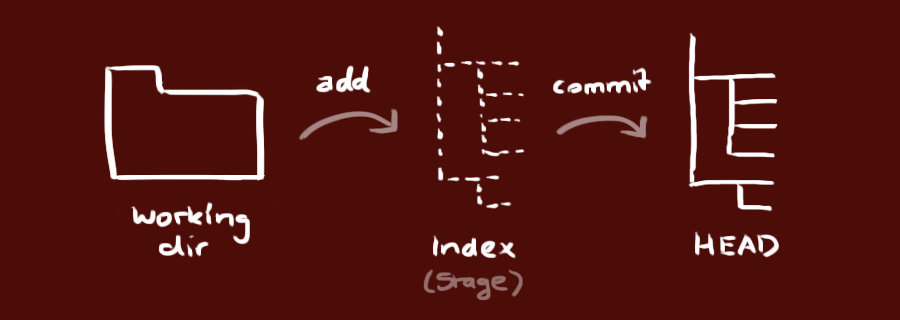

Your local repository consists of three “trees” maintained by git. the first one is your Working Directory which holds the actual files. the second one is the Index which acts as a staging area and finally the HEAD which points to the last commit you’ve made.

Importing a new project

Assume you have a tarball project.tar.gz with your initial work. You can place it under Git revision control as follows.

$ tar xzf project.tar.gz

$ cd project

$ git init

Initialized empty Git repository in .git/

$ git add .

# Tell Git to take a snapshot of the contents of all files under the current directory, or

$ git add -i

# To commit certain files or parts of files in interactive mode.

# This snapshot is now stored in a temporary staging area which Git calls the "index"

$ git commit

# This will prompt you for a commit message

# By submitting a commit message for your changes, you can permanently store the contents of the index in the repository

# Alternatively, instead of running `git add` beforehand, you can use

$ git commit -am "init"

# which will automatically notice any modified (but not new) files, add them to the index, and commit a message says "Hotfix", all in one step

# To see what is about to be committed, using

$ git diff --cached

# Without `--cached`, `git diff` will show you any changes that you’ve made but not yet added to the index

# You can also get a brief summary of the situation with `git status`

$ git status

On branch master

Changes to be committed:

(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

modified: gitAddSomeFile

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: someFileInGitThatHasBeenModified

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

newFileThatIsNotYetInGitIgnoring Files

Some common .gitignore configurations

# Compiled source

*.com

*.class

*.dll

*.exe

*.o

*.so

# Packages

# it's better to unpack these files and commit the raw source

# git has its own built in compression methods

*.7z

*.dmg

*.gz

*.iso

*.jar

*.rar

*.tar

*.zip

# Logs and databases

/tmp

/log

*.log

*.sql

*.sqlite

# Dependency directories

node_modules/

# OS generated files

.DS_Store

.DS_Store?

._*

*~

.Spotlight-V100

.Trashes

ehthumbs.db

Thumbs.db

# Rails.gitignore

Gemfile.lock

/.bundle

/vendor/bundle

/db/*.sqlite3

/db/*.sqlite3-journal

# Jekyll.gitignore

_site/

## sass.gitignore

.sass-cache/

*.css.mapA collection of useful .gitignore templates

Pushing Changes

Your changes are now in the HEAD of your local working copy. If you have not cloned an existing repository and want to connect your repository to a remote server, you need to add it with

$ git remote add origin https://github.com/my/repo.gitTo send those changes to your remote repository, execute

$ git push origin masterIf you want to delete a branch from the server (note the colon before the branch name):

$ git push origin :experimentalReplacing Local Changes

In case you did something wrong, you can replace local changes using the command

$ git checkout -- <filename>

# Replace the changes in your working tree with the last content in HEAD. Changes already added to the index, as well as new files, will be kept.

$ git checkout feature132 flash/foo.fla

$ git add flash/foo.fla

# Another way is to cat the file from git to the normal filename:

$ git show feature132:flash/foo.fla > feature132-foo.fla

# Check out master-foo.fla and feature132-foo.fla

# Let's say we decide that feature132's is correct

$ rm flash/foo.fla

$ mv feature132-foo.fla flash/foo.fla

$ git add flash/foo.flaIf you instead want to drop all your local changes and commits, fetch the latest history from the server and point your local master branch at it like this:

git fetch origin

git reset --hard origin/master

# Or bring a branch to point to a completely different SHA1

$ git reset --hard SHA1_OF_HASHViewing Project History

# At any point you can view the history of your changes using

$ git log

# Often the overview of the change is useful to get a feel of each step

$ git log --stat --summaryManaging Branches

Branches are cheap and easy, so this is a good way to try something out.

$ git branch experimental

# Create a new branch named "experimental"

$ git branch

# Get a list of all existing branches

# The asterisk marks the branch you are currently on

experimental

* master

$ git checkout experimental

# To switch to the experimental branch

# (edit file)

$ git commit -a

# A branch is not available to others unless you push the branch to your remote repository

$ git push origin experimental

$ git checkout master

# (edit file)

$ git commit -a

# At this point the two branches have diverged, with different changes made in each

# You can preview them by using

$ git diff experimental master

# To merge the changes made in experimental into master, run

$ git merge experimental

# If the changes don’t conflict, you’re done. If there are conflicts, markers will be left in the problematic files showing the conflict

CONFLICT (content): Merge conflict in conflictFile

Automatic merge failed; fix conflicts and then commit the result.

# See which files are unmerged at any point after a merge conflict

$ git status

# or

$ git diff --merge

# If you want to use a graphical tool to resolve these issues, you can run `git mergetool`

# Once you’ve edited the files to resolve the conflicts

$ git commit -a

# At this point you could delete the experimental branch with

$ git branch -d experimental

# This command ensures that the changes in the experimental branch are already in the current branch

# If you aren’t sure which branches still have unique work on them — so you know which you need to merge and which ones can be removed, there are two switches to git branch that help:

$ git branch --merged

# Show branches that are not merged in to your current branch

$ git branch --no-merged

# Show branches that are all merged in to your current branch

# You can also create a new branch and switch to it using

$ git checkout -b new-idea

# If you want to rename a local branch

$ git checkout -b crazy-idea new-idea

$ git branch -d new-idea

# Also, if you only specify one branch it’ll rename your current branch

# in `crazy-idea` branch

$ git branch -m super-crazy-idea

# If you regret it, you can always delete the branch with

$ git branch -D super-crazy-idea

# If you delete a branch super-crazy-idea with `-D` you can recreate it with SHA1 hash (You can often find the SHA1 hash using git reflog if you’ve accessed it recently):

$ git branch super-crazy-idea SHA1_OF_HASHAs a general rule, you should try to split your changes into small logical steps, and commit each of them. They should be consistent, working independently of any later commits, pass the test suite, etc. This makes the review process much easier, and the history much more useful for later inspection and analysis, for example with git-blame and git-bisect.

Don’t be afraid of making too small or imperfect steps along the way. You can always go back later and edit the commits with git rebase --interactive before you publish them. You can use git stash save --keep-index to run the test suite independent of other uncommitted changes.

In Git you can drop your current work state in to a temporary storage area stack and then re-apply it later. The simple case is as follows:

$ git stash

# Do something...

$ git stash pop

# Git will automatically create a comment based on the current commit message. If you’d prefer to use a custom message (as it may have nothing to do with the previous commit):

$ git stash save "My stash message"

# If you want to apply a particular stash from your list (not necessarily the last one) you can list them and apply it like this:

$ git stash list

stash@{0}: On master: Changed to German

stash@{1}: On master: Language is now Italian

$ git stash apply stash@{1}Committing to the Wrong Branch

Let’s assume you committed to master but should have created a topic branch called experimental instead. To move those changes over, you can create a branch at your current point, rewind head and then checkout your new branch:

$ git branch experimental

# Creates a pointer to the current master state

$ git reset --hard master~3

# Moves the master branch pointer back to 3 revisions ago

$ git checkout experimentalThis can be more complex if you’ve made the changes on a branch of a branch of a branch etc. Then what you need to do is rebase the change on a branch on to somewhere else:

$ git branch newtopic STARTPOINT

$ git rebase oldtopic --onto newtopicThis is a cool feature, let’s say you’ve made 3 commits but you want to re-order them or edit them (or combine them):

$ git rebase -i master~3Then you get your editor pop open with some instructions. All you have to do is amend the instructions to pick/squash/edit (or remove them) commits and save/exit. Then after editing you can git rebase — continue to keep stepping through each of your instructions.

If you choose to edit one, it will leave you in the state you were in at the time you committed that, so you need to use git commit — amend to edit it.

Note: DO NOT COMMIT DURING REBASE — only add then use --continue, --skip or --abort.

Storing/Retrieving from the File System

Some projects (the Git project itself for example) store additional files directly in the Git file system without them necessarily being a checked in file.

$ man git-hash-object

DESCRIPTION

Computes the object ID value for an object with specified type with the contents of the named file (which can be outside of the work tree), and optionally writes the resulting object into the object database. Reports its object ID to its standard output. This is used by git cvsimport to update the index without modifying files in the work tree. When <type> is not specified, it defaults to "blob".

OPTIONS

-t <type>

Specify the type (default: "blob").

-w

Actually write the object into the object database.

--stdin

Read the object from standard input instead of from a file.

--stdin-paths

Read file names from stdin instead of from the command-line.

--path

Hash object as it were located at the given path. The location of file does not directly influence on the hash value, but path is used to determine what git filters should be applied to the object before it can be placed to the object database, and, as result of applying filters, the actual blob put into the object database may differ from the given file. This option is mainly useful for hashing temporary files located outside of the working directory or files read from stdin.

--no-filters

Hash the contents as is, ignoring any input filter that would have been chosen by the attributes mechanism, including the end-of-line conversion. If the file is read from standard input then this is always implied, unless the --path option is given.

$ echo "test content" | git hash-object -w --stdin

d670460b4b4aece5915caf5c68d12f560a9fe3e4

# At this point the object is in the database.

$ git tag test d670460b

$ git cat-file blob test

test content

$ echo "create test file" > test-file.txt

$ git hash-object -w test-file.txt

f0324dd777f25b8bfadbd236deea4f82bc878370

$ echo "version 1" >> test-file.txt

$ git hash-object -w test-file.txt

7bbe2919089aa9d3a0e8f516a81b624d55b02548

$ echo "version 2" >> test-file.txt

$ git hash-object -w test-file.txt

b8a5143681f66a52092aab1b00640c0d45572877

$ git cat-file -p f0324dd7

create test file

$ git cat-file -p b8a51436

create test file

version 1

version 2

$ git cat-file -p f0324dd7 > test-file.txt

$ cat test-file.txt

create test file

$ git cat-file -p 7bbe2919 > test-file.txt

$ cat test-file.txt

create test file

version 1This can be useful for utility files that developers may need (passwords, gpg keys, etc) but you don’t want to actually check out on to disk every time (particularly in production).

Cleaning Up

If you’ve committed some content to your branch (maybe you’ve imported an old repo from SVN) and you want to remove all occurrences of a file from the history:

$ git filter-branch --tree-filter 'rm -f *.class' HEADIf you’ve already pushed to origin, but have committed the rubbish since then, you can also do this for your local system before pushing:

$ git filter-branch --tree-filter 'rm -f *.class' origin/master..HEADMiscellaneous Tips

tbc

Using Git for Collaboration

Suppose that you’ve started a new project with a Git repository in /home/me/project, and that someone, who has a home directory on the same machine, wants to contribute.

someone$ git clone /home/me/project projectForked

# Create a new directory "projectFork" containing a clone of your repository.Then, someone makes some changes and commits them:

# (someone edit files)

someone$ git commit -aWhen he’s ready, he tells you to pull changes from the repository at /home/someone/projectForked. You can do this with:

$ git pull /home/someone/projectForked master

# The "pull" command performs two operations: it fetches changes from a remote branch, then merges them into the current branch.

# This merges the changes from someone’s "master" branch into your current branch. If you’ve made your own changes in the meantime, then you may need to manually fix any conflicts.Note that in general, you would want your local changes committed before initiating this “pull”. If someone’s work conflicts with what you did since your histories forked, you will use your working tree and the index to resolve conflicts, and existing local changes will interfere with the conflict resolution process (Git will still perform the fetch but will refuse to merge — You will have to get rid of your local changes in some way and pull again when this happens).

You can peek at what someone did without merging first

$ git fetch /home/someone/projectForked master

$ git log -p HEAD..FETCH_HEAD

# Using the "fetch" command allows you to inspect what someone did, using a special symbol "FETCH_HEAD", in order to determine if he has anything worth pulling.This operation is safe even if you have uncommitted local changes. The range notation “HEAD..FETCH_HEAD” means “show everything that is reachable from the FETCH_HEAD but exclude anything that is reachable from HEAD”. You already knows everything that leads to your current state (HEAD), and reviews what someone has in his state (FETCH_HEAD) that you have not seen with this command.

You can visualize what someone did by issuing the following command:

$ gitk HEAD..FETCH_HEAD

# This uses the same two-dot range notation we saw earlier with git log.

# You may want to view what both of you did since you forked.

$ gitk HEAD...FETCH_HEAD

# Three-dot form means "show everything that is reachable from either one, but exclude anything that is reachable from both of them".When you are working in a small closely knit group, it is not unusual to interact with the same repository over and over again. By defining remote repository shorthand, you can make it easier:

$ git remote add theOther /home/someone/projectForked

$ git fetch theOther

# Fetching using a remote repository shorthand set up with git remote, what was fetched is stored in a remote-tracking branch, in this case theOther/master. So after this:

$ git log -p master..theOther/master

# Show a list of all the changes that someone made since he branched from your master branch.

$ git merge theOther/master

# Merge the changes into your master branch

# This merge can also be done by pulling from your own remote-tracking branch, like this:

$ git pull . remotes/theOther/masterNote that git pull always merges into the current branch, regardless of what else is given on the command line.

Later, someone can update his repo with your latest changes using

someone$ git pullNote that he doesn’t need to give the path to your repository; when someone cloned your repository, Git stored the location of your repository in the repository configuration, and that location is used for pulls:

someone$ git config --get remote.origin.url

/home/me/projectGit also keeps a pristine copy of your master branch under the name “origin/master”:

someone$ git branch -r

origin/HEAD -> origin/master

origin/master

someone$ git branch

* masterRule: Topic branches Make a side branch for every topic (feature, bugfix, …). Fork it off at the oldest integration branch that you will eventually want to merge it into.

Finding Who Dunnit

Often it can be useful to find out who changed a line of code in a file.

$ git blame FILESometimes the change has come from a previous file (if you’ve combined two files, or you’ve moved a function) so you can use:

$ # shows which file names the content came from

$ git blame -C FILESometimes it’s nice to track this down by clicking through changes and going further and further back. There’s a nice in-built gui for this:

$ git gui blame FILEMerging Upwards

There are two main tools that can be used to include changes from one branch on another: git-merge and git-cherry-pick.

Merges have many advantages, so we try to solve as many problems as possible with merges alone. Cherry-picking is still occasionally useful.

Most importantly, merging works at the branch level, while cherry-picking works at the commit level. This means that a merge can carry over the changes from 1, 10, or 1000 commits with equal ease, which in turn means the workflow scales much better to a large number of contributors (and contributions). Merges are also easier to understand because a merge commit is a “promise” that all changes from all its parents are now included.

As a given feature goes from experimental to stable, it also “graduates” between the corresponding branches of the software. git.git uses the following integration branches:

-

maint tracks the commits that should go into the next “maintenance release”, i.e., update of the last released stable version;

-

master tracks the commits that should go into the next release;

-

next is intended as a testing branch for topics being tested for stability for master.

-

There is a fourth official branch that is used slightly differently:

pu (proposed updates) is an integration branch for things that are not quite ready for inclusion yet.

Each of the four branches is usually a direct descendant of the one above it.

Conceptually, the feature enters at an unstable branch (usually next or pu), and “graduates” to master for the next release once it is considered stable enough.

The “downwards graduation” discussed above cannot be done by actually merging downwards, however, since that would merge all changes on the unstable branch into the stable one. Hence the following:

Rule: Merge upwards

Always commit your fixes to the oldest supported branch that require them. Then (periodically) merge the integration branches upwards into each other.

This gives a very controlled flow of fixes. If you notice that you have applied a fix to e.g. master that is also required in maint, you will need to git-cherry-pick it downwards. This will happen a few times and is nothing to worry about unless you do it very frequently.

Merge Workflow

The merge workflow works by copying branches between upstream and downstream. Upstream can merge contributions into the official history; downstream base their work on the official history.

There are three main tools that can be used for this:

1 git push <remote> <branch> copies your branches to a remote repository

2 git fetch <remote> copies remote branches to your repository, staying up to date

3 git pull <url> <branch> merges remote topics (Do the fetch and merge in one)

Note the last point. Do not use git pull unless you actually want to merge the remote branch.

Patch Workflow

1 git format-patch -M upstream..topic to turn them into preformatted patch files

2 git send-email --to=<recipient> <patches>

Exploring history

$ git log

commit c3420f6449a990249575d2a3d028a4772060c357

Author: retrcult <an@example.com>

Date: Fri Jun 3 23:41:57 2016 +0800

new post added

commit 325a96d3bc0a324df60b3f02a5969c3d64090262

Author: retrcult <retrcult@github.com>

Date: Fri Jun 3 19:16:25 2016 +0800

change default style

$ git show 325a96d3bc0a

# Use any initial part of the name that is long enough to uniquely identify the commit to see the details about it

$ git show HEAD

# the tip of the current branch

git show experimental

# the tip of the "experimental" branchEvery commit usually has one “parent” commit which points to the previous state of the project:

$ git show HEAD^

# To see the parent of HEAD

$ git show HEAD^1

# Ssame as HEAD^

$ git show HEAD^^

# To see the grandparent of HEAD

$ git show HEAD~4

# To see the great-great grandparent of HEAD

# You can also give commits names of your own

$ git tag v2.5 1b2e1d63ff

# Then you can refer to 1b2e1d63ff by the name "v2.5"If you intend to share this name with other people (for example, to identify a release version), you should create a “tag” object, and perhaps sign it; see git-tag for details.

In Git there are two types of tag — a lightweight tag and an annotated tag. A lightweight tag is simply a named pointer to a commit. You can always change it to point to another commit. An annotated tag is a name pointer to a tag object, with it’s own message and history. As it has it’s own message it can be GPG signed if required. Creating the two types of tag is easy (and one command line switch different)

$ git tag to-be-tested

$ git tag -a v1.1.0

# Prompts for a tag messageAny Git command that needs to know a commit can take any of these names. For example:

$ git diff v2.5 HEAD

# Compare the current HEAD to v2.5

$ git branch stable v2.5

# Start a new branch named "stable" based at v2.5

$ git reset --hard HEAD^

# Reset your current branch and working directory to its state at HEAD^

# You can always see the differences between a local branch and a remote branch:

$ git diff master..myRepo/masterBe careful with that last command: in addition to losing any changes in the working directory, it will also remove all later commits from this branch. If this branch is the only branch containing those commits, they will be lost. Also, don’t use

git reseton a publicly-visible branch that other developers pull from, as it will force needless merges on other developers to clean up the history. If you need to undo changes that you have pushed, usegit revertinstead.

The git grep command can search for strings in any version of your project, so

$ git grep "hello" v2.5

# Search for all occurrences of "hello" in v2.5If you leave out the commit name, git grep will search any of the files it manages in your current directory. So

$ git grep "hello"

# A quick way to search just the files that are tracked by GitMany Git commands also take sets of commits, which can be specified in a number of ways. Here are some examples with git log:

$ git log --name-status

# See only which files have changed

$ git log stable..master

# List commits made in the master branch but not in the stable branch

$ git log v2.5..v2.6

# Commits between v2.5 and v2.6

$ git log feature/132 feature/145 ^master

# View the commits on feature/132 and feature/145 that aren’t on master

$ git log v2.5..

# Commits since v2.5

$ git log v2.5.. Makefile

# Commits since v2.5 which modify Makefile

$ git log lib/foo.rb

# View commits of a particular file

$ git log --author=someone

# To see only the commits by someone

$ git log --grep="Something in the message"

# Search term that appears in the commit message

$ git log --since=2.months.ago --until=1.day.ago

# Commits from the last 2 weeks but not today

# By default it will use **OR** to combine the query, but you can easily change it to use AND (if you have more than one criteria)

$ git log --since=2.months.ago --until=1.day.ago --author=andy -S

# return "something" --all-match

$ git log --pretty=oneline

# To see a very compressed log where each commit is one line

$ git log --graph --oneline --decorate --all

# These are just a few of the possible parameters you can use. For more, see

$ git log --help

# Most projects with multiple contributors have frequent merges, and gitk does a better job of visualizing their history.

$ gitk --since="2 weeks ago" app/The Git Object Database

$ mkdir test-project && cd $_

$ git init

Initialized empty Git repository in test-project/.git/

$ echo "hello world" > Readme

$ git add .

$ git commit -m "initial commit"

[master (root-commit) fe876d7] initial commit

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

create mode 100644 Readme

$ echo "hello world!" > Readme

$ git commit -am "add emphasis"

[master df8a5bd] add emphasis

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+), 1 deletion(-)It turns out that every object in the Git history is stored under a 40-digit hex name. That name is the SHA-1 hash of the object’s contents. The 7 char hex strings here are simply the abbreviation of such 40 character long strings.

We can ask Git about this particular object with the cat-file command.

$ git cat-file

usage: git cat-file (-t|-s|-e|-p|<type>|--textconv) <object>

or: git cat-file (--batch|--batch-check) < <list_of_objects>

<type> can be one of: blob, tree, commit, tag

-t show object type

-s show object size

-e exit with zero when there's no error

-p pretty-print object's content

--textconv for blob objects, run textconv on object's content

--batch show info and content of objects fed from the standard input

--batch-check show info about objects fed from the standard input

$ git cat-file -t fe876d7

$ git cat-file commit fe876d7

tree 75eb93ca2dadfd16966679a9d5714118c77b6219

author retrcult <retrcult@github.com> 1465032128 +0800

committer retrcult <retrcult@github.com> 1465032128 +0800

initial commitA tree can refer to one or more “blob” objects, each corresponding to a file. In addition, a tree can also refer to other tree objects, thus creating a directory hierarchy. You can examine the contents of any tree using ls-tree:

$ git ls-tree fe876d7

100644 blob 3b18e512dba79e4c8300dd08aeb37f8e728b8dad Readme

$ git cat-file -t 3b18e512

# Using SHA-1 hash (a reference to that file's data) above

blob

$ git cat-file blob 3b18e512

hello world$ find .git/objects/

# The contents of these files is just the compressed data plus a header identifying their length and their type. The type is either a blob, a tree, a commit, or a tag.

.git/objects/

.git/objects/df

.git/objects/df/8a5bd442b657193d36f3a319a33a099230e817

.git/objects/pack

.git/objects/3b

.git/objects/3b/18e512dba79e4c8300dd08aeb37f8e728b8dad

.git/objects/26

.git/objects/26/1f66e99f232e2a88fae5c0e8c55873be6938da

.git/objects/fe

.git/objects/fe/876d717b95280ee9b0471198439389b6c74a2e

.git/objects/info

.git/objects/a0

.git/objects/a0/423896973644771497bdc03eb99d5281615b51

.git/objects/75

.git/objects/75/eb93ca2dadfd16966679a9d5714118c77b6219

$ cat .git/HEAD

# It tells us which branch we’re currently on.

ref: refs/heads/master

$ cat .git/refs/heads/master

df8a5bd442b657193d36f3a319a33a099230e817

$ git cat-file commit df8a5bd4

tree 261f66e99f232e2a88fae5c0e8c55873be6938da

parent fe876d717b95280ee9b0471198439389b6c74a2e

author retrcult <retrcult@github.com> 1465032203 +0800

committer retrcult <retrcult@github.com> 1465032203 +0800

add emphasis

$ git ls-tree df8a5bd4

100644 blob a0423896973644771497bdc03eb99d5281615b51 Readme

$ git cat-file blob a0423896

hello world!So now we know how Git uses the object database to represent a project’s history:

-

“commit” objects refer to “tree” objects representing the snapshot of a directory tree at a particular point in the history, and refer to “parent” commits to show how they’re connected into the project history.

-

“tree” objects represent the state of a single directory, associating directory names to “blob” objects containing file data and “tree” objects containing subdirectory information.

-

“blob” objects contain file data without any other structure.

-

References to commit objects at the head of each branch are stored in files under .git/refs/heads/.

-

The name of the current branch is stored in .git/HEAD.

Note, by the way, that lots of commands take a tree as an argument. But as we can see above, a tree can be referred to in many different ways— (1) by the SHA-1 name for that tree, (2) by the name of a commit that refers to the tree, (3) by the name of a branch whose head refers to that tree, etc.–and most such commands can accept any of these names.

The index file

The primary tool we’ve been using to create commits is git-commit -a, which creates a commit including every change you’ve made to your working tree. But what if you want to commit changes only to certain files? Or only certain changes to certain files?

$ echo "hello world, again" > Readme

$ git diff

diff --git a/Readme b/Readme

index a042389..b5205f3 100644

--- a/Readme

+++ b/Readme

@@ -1 +1 @@

-hello world!

+hello world, again

$ git diff --cached

$ git add Readme

$ git diff

$ git diff --cached

diff --git a/Readme b/Readme

index a042389..b5205f3 100644

--- a/Readme

+++ b/Readme

@@ -1 +1 @@

-hello world!

+hello world, again

$ git diff HEAD

diff --git a/Readme b/Readme

index a042389..b5205f3 100644

--- a/Readme

+++ b/Readme

@@ -1 +1 @@

-hello world!

+hello world, again

$ git ls-files --stage

100644 b5205f3e47dc84c3ed1fb3c277ad4868c4c5869c 0 Readme

$ git cat-file -t b5205f3e

blob

$ git cat-file blob b5205f3e

hello world, againgit diff is comparing against the index file, which is stored in .git/index in a binary format, but whose contents we can examine with ls-files.

What git add did was store a new blob and then put a reference to it in the index file. If we modify the file again, we’ll see that the new modifications are reflected in the git diff output:

$ echo "again?" >> Readme

$ git diff

diff --git a/Readme b/Readme

index b5205f3..e74f8dd 100644

--- a/Readme

+++ b/Readme

@@ -1 +1,2 @@

hello world, again

+again?

$ git commit -m "repeat"

[master 7f84961] repeat

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+), 1 deletion(-)

$ echo "goodbye, world" > close.txt

$ git add close.txt

$ git ls-files --stage

100644 b5205f3e47dc84c3ed1fb3c277ad4868c4c5869c 0 Readme

100644 8b9743b20d4b15be3955fc8d5cd2b09cd2336138 0 close.txt

$ git cat-file blob 8b9743b2

goodbye, world

$ git status

On branch master

Changes to be committed:

(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

new file: close.txt

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: ReadmeBy default git commit uses the index to create the commit, not the working tree; the “-a” option to commit tells it to first update the index with all changes in the working tree.

Since the current state of close.txt is cached in the index file, it is listed as “Changes to be committed”. Since file.txt has changes in the working directory that aren’t reflected in the index, it is marked “changed but not updated”. At this point, running git commit would create a commit that added close.txt (with its new contents), but that didn’t modify file.txt.

Also, note that a bare git diff shows the changes to file.txt, but not the addition of close.txt, because the version of close.txt in the index file is identical to the one in the working directory.